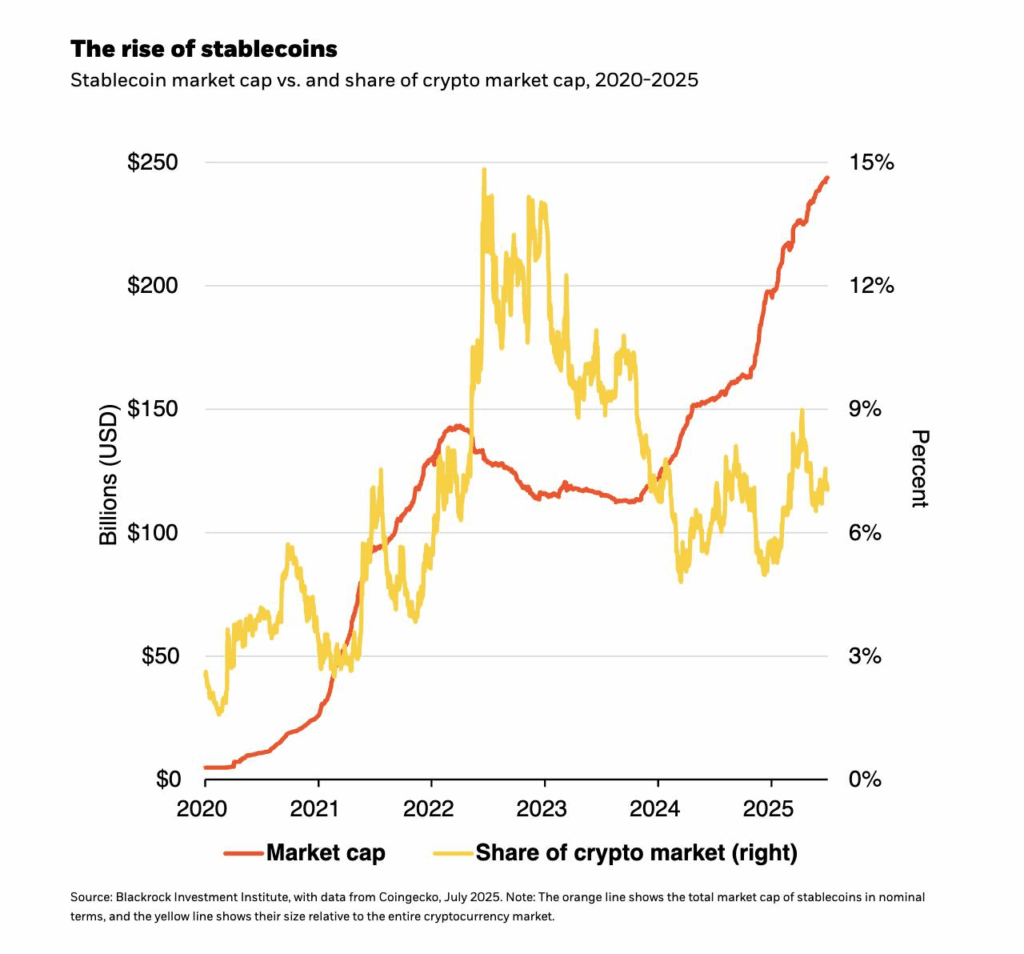

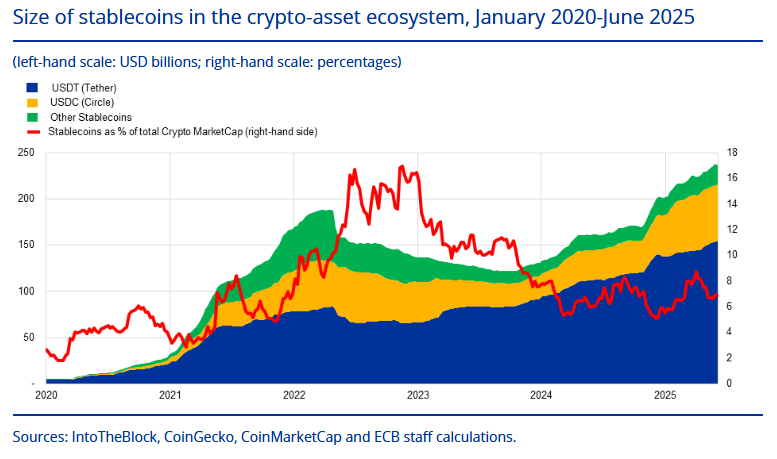

In a recent speech in Portugal, Christine Lagarde — president of the European Central Bank (ECB) — gave a stern warning about the emergence of stablecoins, stating that they could lead to the creation of “new private currencies.”

These stablecoins, which are tokens (digital tokens) backed by government currencies (fiat), pose a serious threat to both the monetary sovereignty of states and the “common good” of money.

For this reason, she called for them to be regulated at the global level. Throughout her statement, it becomes clear that the main risk of these digital assets is their popularity among citizens, who see them as a relatively simple way to gain exposure to the “lesser evil” fiat currencies — with the dollar at the top of the list.

According to Lagarde, this success of stablecoins in cryptocurrency markets undermines the effectiveness of central bank monetary policy, as the amount of money circulating through traditional commercial banks is reduced.

“I think we are falling victim to a confusion between money, means of payment and payment infrastructure, and this is exacerbated by the technology that is used — certain technologies in particular. I see money as a public good and we as public officials who have taken on the responsibility of protecting it.” “My fear is that this confusion that I mentioned could lead to the privatization of money. I do not think that is why we were appointed, nor is it good for this public good that is money.”

The privatization of money – Stablecoins are not currencies

Another interesting point in Christine Lagarde’s statement is that — like Andrew Bailey (governor of the Bank of England) — she claims that stablecoins “pretend” to be currencies, when in fact they are not. According to them, stablecoins cannot be considered real currencies because they are not issued by public authorities, but by private companies — that is, by the market itself.

The problem lies in this perception of money as a public good; a good whose management, guarantee and protection is the task of central banks.

Money as a “public good” and state monopoly

The concept of “public good” is often associated with the general interest. Contrary to what central bankers claim, the general interest is not identical with the state’s monopoly control of money.

In fact, any currency that is controlled at will by a central authority without accountability is a threat to the general interest.

Let us first define what “public good” means.

According to Frédéric Bastiat — a prominent figure of classical liberalism — the public good includes everything that precedes and goes beyond positive legislation: freedom, property, and the protection of the personality (i.e., the dignity, life, and uniqueness of each human being). It is everything that positive law (a creation of the state) is supposed to protect — not undermine, as it often does.

The General Interest and the Market Order

For classical liberals and Austrian economists, the general interest lies in the spontaneous institutional forms that humans have developed over time.

Any attempt by the legislator to dismantle and redesign these institutions in the name of a “new collective general interest” constitutes an attack on the authentic public purpose that has emerged through human action.

This is especially true of money—one of the first institutions to be subjected to state manipulation. For the monopoly of money is the most powerful form of control that an elite can exert over the population.

As Hayek wrote: “In a free society, the common good consists chiefly in facilitating the pursuit of unknown individual ends… The most important of the public goods for which government is required is not the immediate satisfaction of particular needs, but the securing of conditions under which individuals and groups can mutually satisfy their needs.”

History shows that the central banking system has repeatedly undermined the public interest—that is, property, liberty, and the protection of the individual—through the politicization, devaluation, and centralized management of currency.

The result of these policies is that today’s fiat currency (the creation of a state monopoly) no longer fulfills the essential characteristics of money:

- it does not reflect the relative scarcity of goods,

- it does not function effectively as a medium of exchange,

- nor as a store of value.

But what if the role of central banks was precisely to destroy the “public good” of money, using it as a tool of legal plunder through inflation, distorting interest rates, and restricting individual liberties?

In this context, the promise of a digital euro (CBDC) seems to be the culmination of this coordinated attack on the real public good. Private Currencies and the Fear of Competition

Hayek, in his work The Denationalization of Money, wrote: “If we are to preserve a functioning market economy (and with it individual freedom), nothing is more urgent than to dissolve the unholy marriage between monetary and fiscal policy, sanctified by the victory of ‘Keynesianism.’”

Contrary to what Christine Lagarde seems to argue, a monetary system of private currencies would be the best way to protect the “public good” and the general interest.

Why? Because, by giving citizens the choice, they would choose the best currency the market could offer them:

- a scarce currency, reflecting the scarcity of the world,

- neutral,

- tax-free,

- incorruptible and stable,

- a currency in which we can store our time and energy, postponing its use to the future.

Ideally, this means a currency outside state control and beyond the corruptions of human power.

This is what Austrian economists, such as Hayek, argued in The Denationalization of Money: the free circulation and competition between private currencies would lead to a higher quality of money, thanks to the mechanisms of spontaneous choice of citizens – that is, the spontaneous order of the market.

In this context, the dollar, the euro, and any other fiat currency, would have no chance.