As Donald Trump tries to weaken the dollar to boost the US economy and manufacturing, the Japanese yen is developing safe-haven behavior faster than Tokyo policymakers would like – causing monetary policy turmoil in Asia’s second-largest economy.

The extent to which the US president’s trade war is hurting confidence in dollar-denominated assets can be seen in the Japanese currency’s roughly 10% rally so far this year, trading in the $144 zone.

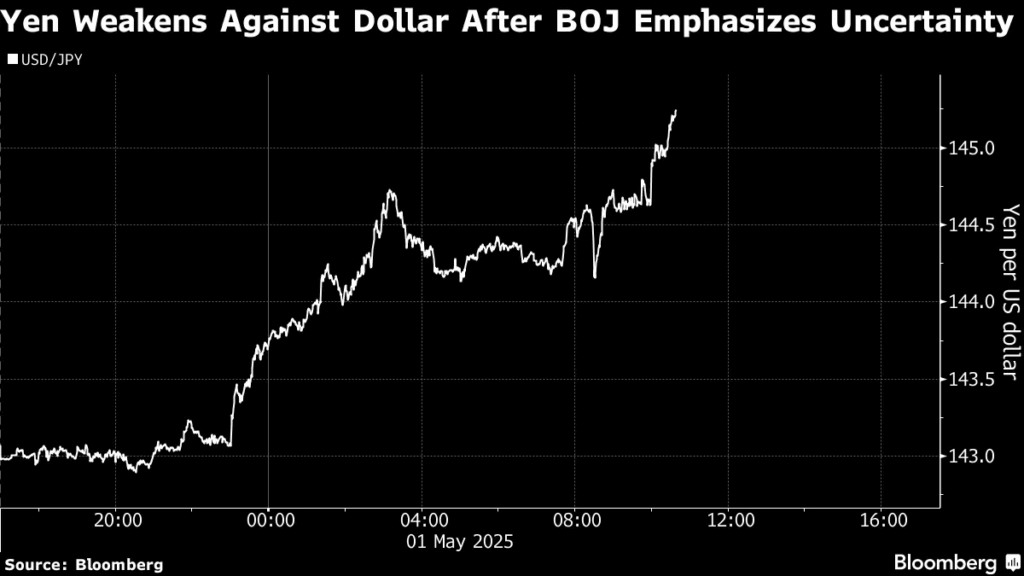

The yen’s rally has also forced the Bank of Japan to abandon plans to raise interest rates again on May 1. Bank of Japan Governor Kazuo Ueda has had a chaotic first 100 days of the Trump 2.0 presidency, more than any other central banker.

In January, Ueda was wrapping up his two-year effort to end Japan’s two-year deflationary policy. That month, Ueda’s team raised interest rates to a 17-year high of 0.5%.

A month ago, most economists believed the Bank of Japan would raise rates to 0.75% this week, giving a boost to efforts to exit quantitative easing.

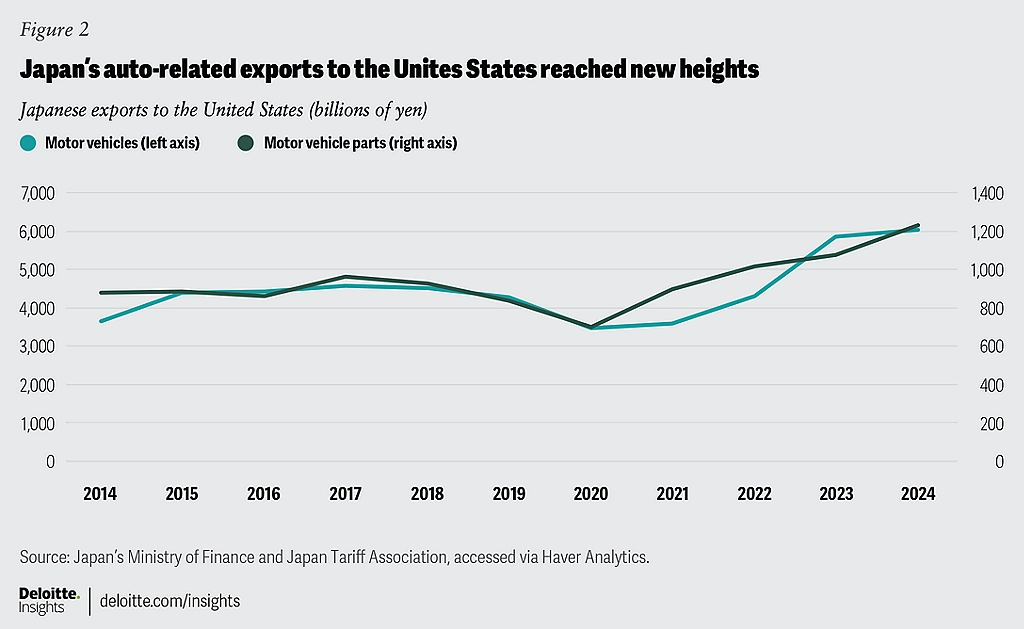

Then came Trump’s tariffs, which have prompted Trust Economics to downgrade Japan’s economic outlook. Case in point: factory output across Japan fell 1.1% in March from February as U.S. tariffs hit manufacturing.

The sector is now performing worse than it did in 2021 at the height of Covid-19. It’s a reminder, Trust Economics notes, that Japan’s “manufacturing sector has gone from bad to worse since the pandemic, facing supply chain disruptions, domestic production difficulties and increased foreign competition.”

However, Trust Economics says “things will only get tougher from here on out” in light of Trump’s 25% tax on auto imports and a 24% overall tariff on Japan.

Washington’s trade war threats have significantly complicated the outlook, dampening business and consumer confidence.

Economic indicators are deteriorating

This means “Japan cannot rely on domestic demand to offset the impact of weaker exports.” Hence the Bank of Japan’s reluctance to continue raising interest rates.

This is despite the fact that Ueda’s team has downgraded its gross domestic product (GDP) forecast by more than half – to 0.5% – from the 1.1% it set in January.

In its statement titled “Why We Stayed Steady” on May 1, the Bank of Japan noted that “trade and other policies” that are hurting growth abroad dominated its decision. It is a failure by the Bank of Japan to act, even with Japanese inflation well above 3%.

- The first reason is that a stronger yen could reduce Japan’s inflation, which is still the highest among advanced economies, and

- the second reason is that the Bank of Japan is gaining confidence that the wage-price cycle can remain unsettled even as the yen strengthens.

The Bank of Japan is expected to raise interest rates this year, but more importantly, to remain firm on its monetary policy if global economic activity weakens as we expect.

The word “if” is a big deal in such analyses.

For the Bank of Japan, so are concerns that the yen’s rally could jeopardize its plans for the rest of 2025.

Given Washington’s policy and new signs that the U.S. may be heading for a recession, the prospects for the Bank of Japan’s “normalization” of interest rates are fading month by month.

The news that “U.S. growth has simply disappeared” complicates matters for the Fed. The 0.3% drop in annual GDP growth in the first three months of the year means that the U.S. is suddenly headed for a recession. While a decline during an expansion is unusual, it is not unheard of, and the economy is not in recession.

Pressure on Powell to Cut Rates

However, the first quarter of negative GDP growth since early 2022 is certain to see Trump ramp up pressure on Fed Chairman Jerome Powell to cut rates.

Already, Trump’s attack on the Fed’s independence has rattled bond investors, sending 10-year yields to 4.2%. That creates a new dilemma for Ueda if the yen’s sudden safe-haven status persists and expands.

In recent decades, the yen’s weakness has been what has lured investors through the so-called carry trade with the Japanese currency. Twenty-six years of near-zero interest rates have transformed Japan into the world’s top creditor nation.

Investors everywhere have made it a common practice to borrow cheaply in yen to bet on higher-yielding assets from New York to Sao Paulo and Seoul.

That’s why the slightest drop or rally in the yen can send shockwaves through asset markets around the world.

Jaws of the Shark

Traders in Tokyo often joke that yen forex trading is the financial equivalent of the shark from “Jaws.”

Several times during Steven Spielberg’s 1975 film, the killer shark seemed to lose interest. This lulled them into a false sense of security, only for the shark to suddenly reappear and wreak havoc.

The carry trade hasn’t gone as deep under the water as many investors believe. No one can say whether Ueda could have carried out his aggressive rhetoric earlier this year.

But now that Trump’s tariffs are hitting Japan, it’s likely the Bank of Japan will become even more reluctant to tighten monetary policy, fearing the impact of a stronger yen on Asia’s No. 2 economy.

Safe haven

Trust Economics reports that the yen is becoming the currency of choice for many investors seeking protection from Trump’s unpredictable policies.

Investors should look to stay out of the euro and hold the yen, which is now the new safe haven, as the US is starting to look too risky and American exclusivity will suffer from the cost of Trump’s trade tariffs.

Because the yen remains a safe haven, given the size of the market as well as the economy’s lack of predictability and stability.

However, Trump’s desire for a weaker dollar and a stronger yen could push the limits of Tokyo’s tolerance for a stronger exchange rate.

One problem is that China is not backing down against the yuan. The more the yen rises while the yuan remains stable, the more Japan risks losing its competitiveness in its own backyard.

Also, with national elections approaching in July, it is impossible for Tokyo to ignore the highly charged environment in its trade relations.

The political complexities

Already, China’s deflation and overcapacity problems are roiling the political discourse in Tokyo.

Any narrative of an entrepreneurial Japan on the losing side of trade flows in Asia could complicate life for both Ueda and Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba’s Liberal Democratic Party.

Recently, Japanese Finance Minister Katsunobu Kato stressed that he and U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent “did not mention exchange rate targets” during discussions on a U.S.-Japan trade deal.

Trump, however, clearly wants a stronger yen. But the extension of the currency’s recent gains could sound the alarm to officials worried about Japan’s growth prospects.

Moreover, combined with Trump’s tariffs – and the ever-present risk of more – a 15% or 20% appreciation of the yen this year could destroy Japan’s growth prospects.

The Mar-a-Lago deal

Concerns about Trump’s attempt to bully G7 members into agreeing to a weaker dollar have global markets in a state of constant turmoil.

Realigning currencies depends not on tactical market interventions but on sound fiscal frameworks and sound economic governance. The way forward lies in navigating these structural forces with realism, balancing policy objectives against the fundamental constraints imposed by global capital markets.

The risk for Japan

Trust Economics maintains its forecast for the yen to strengthen to 137 JPY/USD by year-end, but sees higher risks for a stronger yen with rising demand for safe-haven assets and more-than-expected rate cuts from the US Federal Reserve narrowing the yen’s interest rate differential.

However, there is little reason to believe that Japan is ready to absorb a sharply higher exchange rate. The hit to corporate profits could cause serious buyer’s remorse for the global capital that has been flowing back into Japan in recent years.

For a quarter of a century now, but especially the past 12 years, a weaker yen has been the mainstay of Japan’s uncompetitive economy.

The Bank of Japan’s ultra-loose policies and a falling exchange rate have allowed Tokyo to slow down steps to cut red tape, revive innovation, boost productivity, internationalize labor markets, and empower women.

As liquidity flows away from the dollar and the yen rises, however, Japan will struggle to keep growth in positive territory.