New products reminiscent of the subprime era and which may create negative vicious cycles and crises are being launched by global bankers, reaping temporary benefits but at the same time questioning the stability of the international financial system. SRT – synthetic risk transfer is one of the hottest financial engineering tools today.

The SRT tool works as follows:

- A bank transfers some or all of its bad loans to other vehicles in order to reduce the capital it must allocate for regulatory purposes.

- The loans remain on the bank’s balance sheet, but the SRT buyer assumes the obligation to cover part of the losses if the loans are not serviced.

- The buyers are investors such as insurance companies, hedge funds and (increasingly) private equity funds, who assume the risk in exchange for a fee.

Proof that SRTs have now reached the “big leagues” is that this exotic form of securitization received special mention in the IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report in October.

In a special context, International Monetary Fund analysts noted (emphasis added): “A growing number of banks worldwide have begun to use synthetic risk transfers (SRTs) to manage credit risk and reduce capital requirements. SRTs transfer the credit risks associated with a portfolio of assets from banks to investors through a financial guarantee or credit bonds, while the loans remain on the banks’ balance sheets. Through this protection, banks can claim substantial capital relief and reduce regulatory burdens.

However, these transactions can create risks to financial stability that need to be assessed and monitored. Globally, more than $1.1 trillion in assets have been synthetically securitised since 2016, with nearly two-thirds in Europe.

In the United States, activity increased in 2023 and is expected to accelerate as the regulatory landscape becomes clearer. In Europe, loans to businesses and small and medium-sized enterprises, a well-known and stable class of loans for investors, underpin the bulk of issuance; recent transactions in the United States have focused on retail loans, particularly auto loans.

In Europe, SRT issuers include global systemically important banks and large banks, while in the United States, regional banks issue SRTs.”

As the IMF report suggests, SRTs are at the heart of the growing relationship between private finance and banks.

In fact, while at some levels they are competitors, SRTs are fundamental to how they can work together and explain why we are seeing more collaborations between the $3 trillion private finance industry and the traditional banking industry.

What exactly does this financial engineering entail, how long has it been going on, why has it only recently exploded, and how dangerous is it?

In fact, synthetic risk transfers (SRTs) are not as new as their relatively recent name suggests. They were also often called “significant risk transfers,” but both terms are versions of what used to be called CRTs, or “credit risk transfers” or “capital relief transactions.”

In the heyday of the 2010s, these transactions were commonly called “regulatory capital transactions” or “capital relief transactions.” Even before then, the phenomenon manifested itself as balance sheet securitizations or synthetic collateralized loan obligations.

But how does a modern synthetic risk transfer work?

Let’s say a bank has a huge amount of corporate loans, mortgages and credit card debt on its balance sheet, but the regulatory capital it needs to set aside to insure itself against losses is staggering.

Most importantly for the people running the bank, this affects the bank’s profitability ratios and, therefore, the bankers’ bonuses.

- The bank then selects a €1 billion portfolio of relatively high-quality corporate loans that it has as a reference pool.

- It then finds a group of investors led by Generic Greek God Capital (GGG Capital) who, for a fee, will insure the first 10% of losses on this portfolio, known as the “junior tranche.”

- In other words, GGG Capital will cover the first $100 million in losses in exchange for periodic payments, say 3 to 10 percentage points above the benchmark rate (the level being determined by the riskiness of the underlying loans).

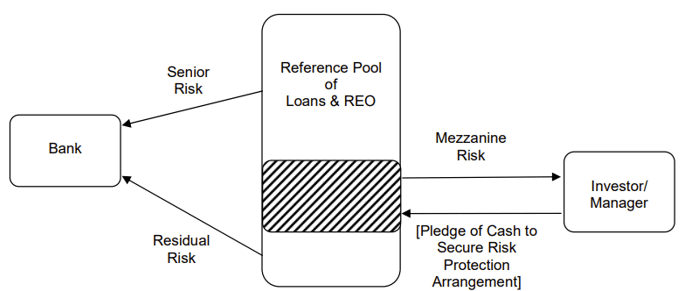

- A fund manager typically has to deposit the entire insured amount with a third-party custodian—the escrow account in the diagram above—but larger and more powerful counterparties (such as an actual insurance company) can make an “unfunded” deal.

- The advantage for GGG Capital is that it can earn returns of 10 to 15% without much effort (beyond initial due diligence on the loan portfolio).

- The loans remain on the bank’s balance sheet, so the bank is responsible for ongoing monitoring of the borrowers.

- And if these are not serviced, the bank will have to manage the recovery, as the loans remain on its balance sheet.

- GGG Capital is simply there to insure the bank against losses (up to a point).

- For the bank, the advantage is (if the structure qualifies as a “real” risk transfer) that regulators will subsequently require less capital for the loans.

- To comply with risk retention rules, the bank will have to retain a portion of its own SRT, but let’s leave that aside for now.

- A €1 billion loan portfolio might require €105 million in capital before any SRT deal—assuming full risk weighting and a 10.5% core capital requirement—but with GGG Capital responsible for the first €100 million in losses, it might only need to allocate around €15 million in capital.

This allows the bank to make more loans, return money to investors, or simply improve its capital ratios and reduce risk. In other words, it looks like a more agile and efficient bank, thanks to some clever behind-the-scenes engineering.

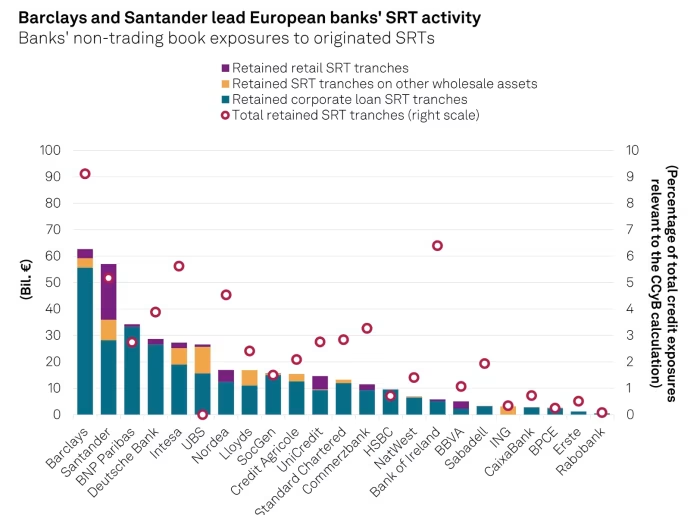

A recent S&P Global report measured activity based on the size and type of SRT holdings held by various banks on their balance sheets:

In fact, this market has now become so large, established and vibrant — and prices so cheap because of the money flowing into these deals — that SRT experts say the rare banks that avoid these transactions stand out.

Even the European Systemic Risk Board now says that “the importance of the SRT securitization market for European banks and the European economy cannot be underestimated.” But some believe that the days of this rare area of European financial dominance will soon be over, because the Americans are coming.

On September 28, 2023, the Federal Reserve published a seemingly innocuous legal interpretation titled “Frequently Asked Questions on Regulation Q,” with the even more repugnant subtitle “Capital Adequacy of Bank Holding Companies, Savings and Loan Holding Companies, and State-owned Member Banks.” It was a surprise hit.

This guidance was a de facto endorsement by the Fed of the capital relief that SRTs can provide, giving the US market a huge boost. Since then, firms like JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley have jumped in, with Pimco predicting that by the end of next year, US SRT issuance will likely match Europe’s volume.

The US SRT market, however, will be a bit different.

While there has been a wave of high-profile deals from leading banks (as “high-profile” as that can be in this relatively opaque market), most expect US issuance to be dominated by regional banks, playing out differently.

In the United States, banks have strategically used SRTs to free up capital and liquidity after the 2023 regional bank crisis, reducing exposure to long-dated, fixed-rate assets to manage the risk of a deposit run.

These SRTs typically take the form of cash securitizations.

In Europe, by contrast, most European banks are strategically using SRTs to optimize capital utilization, given ongoing capital constraints that limit their ability to provide credit to key customer segments.

The “X factor” in the US is what will happen with the Basel III rules, known as “Endgame”. Now that Donald Trump has won the presidency, the details of the regulations may be overturned, easing capital pressures on many US banks and reducing the need for SRTs. Nevertheless, most expect the Endgame rules to be implemented, albeit in a limited form. Even if they are dramatically weakened, many US banks will still need to improve their capital ratios.

We also note that raising equity, another option that banks could consider to improve their capital ratios, is both dilutive and expensive in a high-interest-rate environment. SRTs allow banks to achieve regulatory capital relief and improve their ratios without diluting their shareholders.

Private credit fund participation

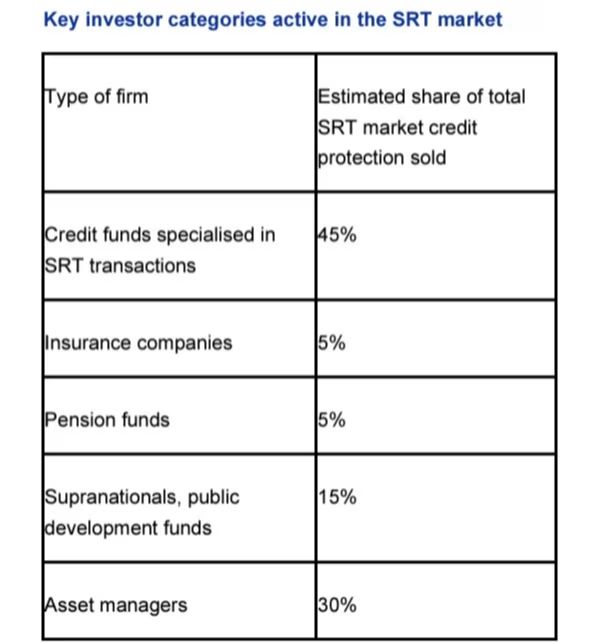

Historically, the main buyers of SRTs have been pension funds and a few hedge funds or asset managers focused on the credit sector. More recently, insurance companies have become more important, but the biggest change is the growing participation of private credit funds.

The IMF estimates that private credit funds are now the “dominant buyers” with a market share of over 60%. Here are the ESRB’s estimates of the SRT buyer base by June 2023: As the ESRB noted: “The profile of demand is clearly composed of professional and specialized credit portfolio managers. The survey also shows that the number of investors is steadily increasing in almost all categories. Market participation is limited to professional investors who appear to be prepared to understand and assume the risks associated with these structures.”

However, people close to the market say the growing presence of private credit funds — which have an excess of cash due to the popularity of the asset class but are struggling to find attractive deals — has been felt.

Of course, the real concern is not that some private credit funds might not achieve the returns they hope for. These funds are staffed by professionals, and their investors are primarily large institutional investors. Caveat emptor, etc. The concern expressed by some is that SRTs actually make the financial system more unstable — the opposite of their intended purpose.

Risk cycling

There are many aspects to these concerns. The IMF provides a good summary in its latest Global Financial Stability Report:

“First, SRTs can create negative vicious circles during crises. For example, there is evidence that banks provide leverage to credit funds to buy credit-linked notes (CLNs) issued by other banks. From a financial system perspective, such structures retain significant risk within the banking system but with lower capital coverage. The size of these interconnections is difficult to assess, as the market remains opaque, with only a fraction of deals being made public and without a central database for SRTs.”

“Second, SRTs may mask the degree of resilience of banks, as they increase a bank’s regulatory capital ratio while its overall capital level remains unchanged. Increased use of SRTs may reflect an inability to raise capital organically due to weaker fundamentals and profitability performance.

Furthermore, overreliance on SRTs exposes banks to business challenges if the liquidity of the SRT market dries up.” “Currently, the asset portfolios being securitised appear to be of higher quality. However, there is concern about asset quality degradation.

Financial innovation may lead to the securitisation of riskier portfolios, creating challenges for banks with less sophisticated risk management tools, because some more complex products make the identity of the ultimate risk holder less clear.”

“Finally, while lower bank-level capital requirements make sense due to risk transfer, regulatory arbitrariness across sectors can reduce capital buffers in the broader financial system while overall risks remain largely unchanged. Financial sector supervisors should closely monitor these risks and ensure the necessary transparency about SRTs and their impact on banks’ regulatory capital.”