The trade war is just one phase of a broader currency war that has been going on for less than 20 years.

- The first currency war was fought in the 1920s with the collapse of the gold standard (and was the prelude to two world wars),

- The second was marked by the Nixon Shock and the decoupling of gold from the dollar in the early 1970s.

- The third was triggered by the financial crisis of 2008/2009 and is ongoing.

Last week, President Donald Trump made a significant move. He appointed Stephen Miran, head of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, to a position on the Board of the Federal Reserve (Fed).

The international media has highlighted the importance of this move, with many analyses focusing on whether the Fed’s independence and the well-known alarmist rhetoric are threatened.

The “juice” is elsewhere: What might Trump’s plans to overhaul the Fed mean for international trade relations, and what role might Miran play?

This could lead to an acceleration of the bull market in gold, currencies, mining and energy.

In these sectors, those who have identified the logic of currency wars are ahead of both human and algorithmic traders, who are still loaded with overvalued positions in Big Tech and AI.

Setting the Battleground

“Currency wars” involve the actions of a country’s government with specific policies to devalue its currency.

The goal is to subsidize domestic exporters so that they can sell cheaper than their competitors, taking into account exchange rates – that is, to reduce currency risk.

Other countries usually strike back first, also devaluing their own currency.

Asian economies have been doing this for decades, while the US has essentially “disarmed” itself—mainly through behind-the-scenes pressure from Wall Street and the lobbying that influences the political class.

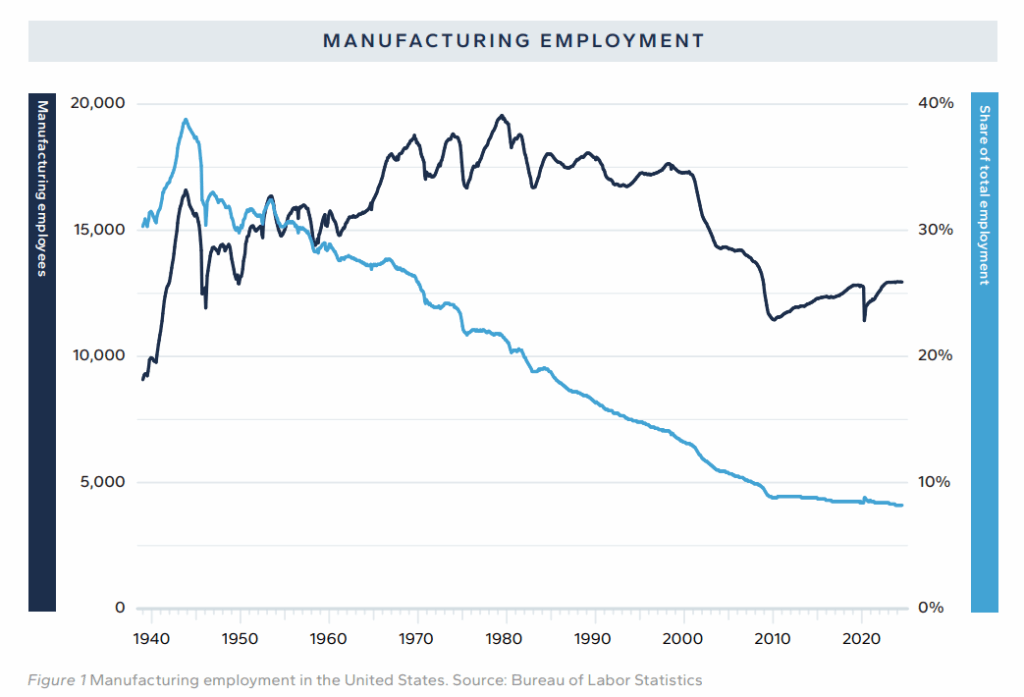

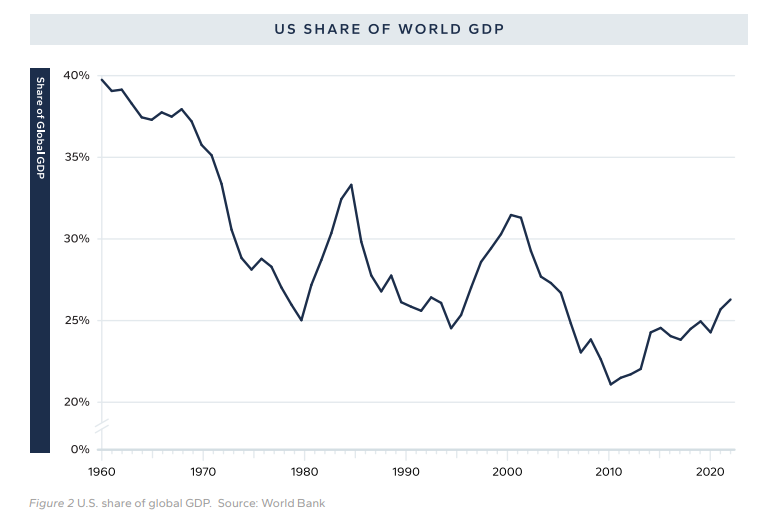

The consolidation of the dollar as the dominant trade and reserve currency has been the main catalyst for deindustrialization, fiscal diversion through congressional decisions, and the overgrowth of the financial sector.

All of this is related to the dollar’s role as a store of value. Currency conflicts can escalate into a war where, in the end, all currencies are devalued against gold.

The Hour of Gold

Gold has historically been (and probably will be again) the means of settling international trade. The China-US trade relationship is by far the most important in the world.

To avoid devastating tariffs and a Chinese devaluation that would reignite the old pattern of currency war, China might agree to a currency clause in a trade deal with Trump. Such a clause could pave the way for settling international trade imbalances in gold.

Advantages for both sides:

- For countries with a trade surplus: Settling trades in gold could impose a lasting truce on currency wars.

China would boost domestic confidence in its fragile financial system and limit the risk of a deflationary debt crisis by more clearly recognizing gold as a store of value.

Other countries with large surpluses, such as Japan, Korea, and Germany, could gain more fiscal space to address the challenges of their aging populations and the crisis in their pension and welfare systems through devaluation against gold.

- For countries with trade deficits: The United States, by paying for Chinese imports in gold, would assure China that it is receiving real money — real savings, not printed money.

Gold cannot be devalued. If the dollar were to depreciate against gold, it would significantly raise the price of imports in dollars, prompting American consumers to prefer domestic products. Such a devaluation would also give the United States more fiscal space and reduce the risk of a debt crisis from the current cycle’s over-leveraging of credit conditions.

One can imagine a world where paper money dominates domestic transactions, while gold dominates international settlement.

China has been quietly accumulating gold for decades—and at a significant pace recently—in preparation for this eventuality.

American Birthright: Local Production of Goods, Gold, Metals, and Oil

Trade policy and monetary policy are most effective when they are aligned.

One without the other is like trying to box with one hand tied behind your back. Trump understands this.

He is eager to exert greater control over the Fed, because without its help, his goals for adjusting trade relations would fall short of expectations.

American Birthright—maximum local production of energy and raw materials—would not only provide the necessary materials to bring back industries that had been moved to China. It could also increase production and jobs, and stem the flood of dollars that has been flowing abroad for decades—dollars that, when they return to Wall Street, fuel financial “bubbles.”

These “bubbles” widen the politically dangerous income gap, strengthening the dollar, asset prices, and production costs.

“Bubbles” also make the U.S. manufacturing sector uncompetitive internationally because they encourage excessive share buybacks at the expense of more uncertain—but job-creating—investments in R&D and capital projects.

Finally, “bubbles” distract the public from real investments that can improve living standards and focus attention on “pump-and-dump” stock market games (which artificially inflate prices and then dump stocks on the ignorant) that are more widespread than many people realize.

To keep growing, bubbles need an endless chain of “bigger fools.”

The last in the chain end up being the big victims. And when the supply of new “fools” runs out, the supposed paper wealth disappears.

Reading between the lines of Stephen Miran’s text, it seems that he understands how destructive bubbles can be to the sustainability of the economy.

The Miran-to-Fed Switch

Last week, Trump made a big move to… enlist the Fed in the currency war. The move could even be a stepping stone to nominating Stephen Miran as Fed Chairman when Jerome Powell’s term ends in May 2026.

It could be a test for a bigger role. Trump often surprises with his choices. Even if he chooses another candidate to replace Powell, the pattern is clear: the Fed will be used for the long-awaited rebalancing of trade flows.

Moving from his position as head of the White House Council of Economic Advisers to the core of Fed policymaking, Miran will bring a radical perspective to FOMC meetings: he understands that the dollar’s status as a reserve currency has shifted from “over-privileged” to “over-burdened.”

This is evident in his public writings, speeches, and interviews. Most Fed positions are held by academics or financial industry veterans who respect the established monetary orthodoxy. That orthodoxy needs a radical overhaul.

Miran’s “Dollar Trap” Theory – The Triffin Dilemma

Miran’s analysis focuses on the so-called Triffin Dilemma.

As the global reserve currency, the dollar must meet international demand for transactions and savings. This creates permanent trade deficits in the United States — not out of waste, but out of structural necessity.

Under the current regime, the global economy requires dollars to function. Americans must supply them by importing more than they export. This keeps the dollar artificially strong, making U.S. industry less competitive, while foreign producers gain an advantage in the currency war.

Previous Fed governors saw this as an inescapable reality. Miran sees it as a problem that can be solved — but it requires coordinated action between fiscal and monetary policy.

Currency Manipulation as Economic Warfare

Where previous governments have limited themselves to diplomatic protests against currency manipulation, Miran advocates the use of tariffs as strategic leverage.

He views exchange rates not as pure market outcomes but as policy tools that can be adjusted through concerted pressure.

His central conclusion from A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System (November 2024) is that tariffs alone often fail, because currency depreciation can negate their effects.

A 25% tariff becomes useless if the targeted country’s currency weakens by 25%.

Miran’s solution is a sequence: first use of tariffs to create bargaining leverage, then coordinated currency adjustments to secure the desired economic outcome.

We saw this clearly on “Liberation Day,” April 2, where high tariffs were used as a bargaining tool.

Why does Trump’s appointment matter?

Despite his bold vision, Miran is aware of the risks of implementation. In his paper, he emphasizes “gradual pace” and careful sequencing of moves to avoid financial market chaos.

“There is a path to implementing these policies without substantial adverse consequences,” he noted, “but it is narrow and will require offsetting the monetary effects of tariffs and either gradual implementation or coordination with allies or the Federal Reserve on the dollar.”

Previous Fed positions have left monetary policy to the Treasury Department. Miran’s appointment removes that separation.

For the first time in decades, there is someone on the Fed board who sees currency intervention as a core responsibility rather than an emergency function.

Market Implications

Currency traders and international investors are facing a new reality: the Fed may no longer be a passive observer of exchange rate movements.

If Miran’s views influence its policy, foreign exchange markets could become an active battleground rather than a neutral price-setting mechanism.

The implications extend beyond the forex market.

Bond, stock and commodity markets depend on assumptions about central bank behavior.

A Fed that actively manages the dollar exchange rate operates under completely different parameters than a Fed that focuses only on domestic inflation and employment.

A Fed engaged in currency wars—with the possibility of a “peace deal” on gold trading—means:

- Less forward guidance on interest rates, which reassures bond traders.

- Fewer outdated Keynesian “factory economy” models, which failed to predict the worst inflation in decades in 2021.

- More recognition that the dollar’s status as a reserve currency comes at a cost: deindustrialization, trade imbalances, fiscal profligacy, and widening wealth inequality.

What does all this mean for portfolios?

As Trump seeks to modify international trade agreements, demanding tougher terms in favor of the American worker, we will see increased volatility in currencies and stocks.

Perhaps even a technical recession (with Trump achieving the significant interest rate cuts he is pushing the Fed to make).

If economic adversaries respond to tariffs and Fed rate cuts by depreciating their currencies, then investors worldwide have yet another reason to hold gold as a hedge against currency volatility.

There will be ample profit opportunities from well-positioned companies in the natural resources sector.