The Illusion of Black Gold

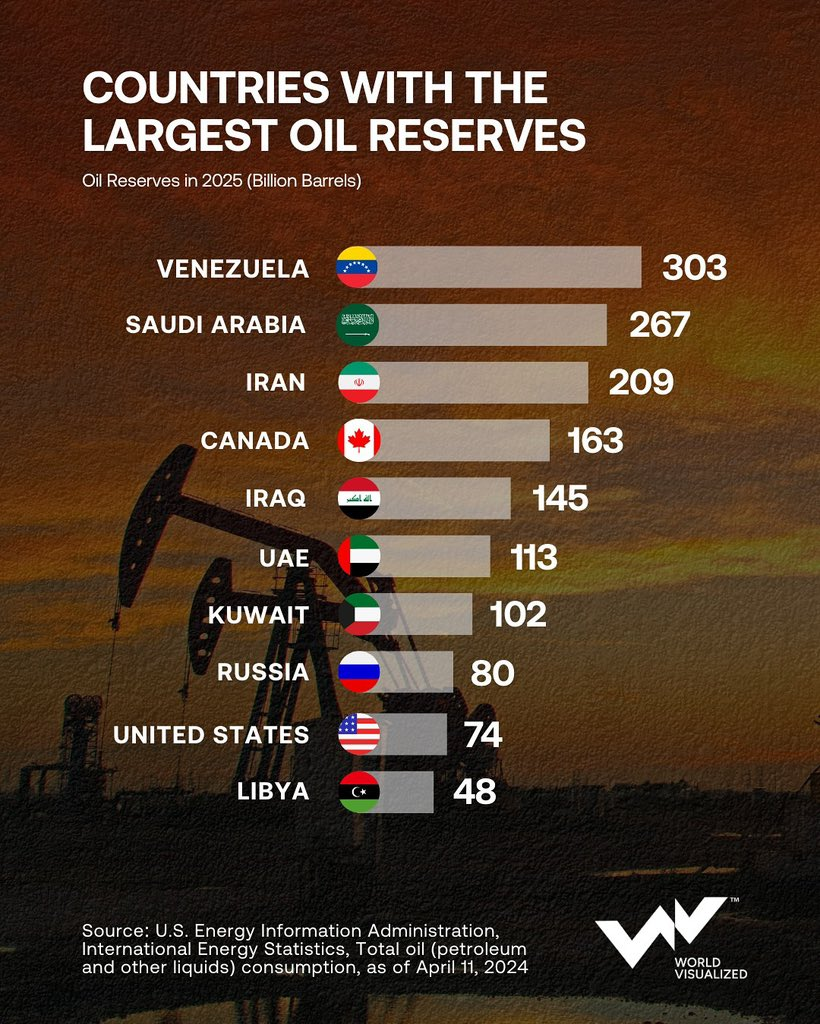

The first and greatest paradox is geological. As confirmed by data from OPEC and the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), Venezuela has the largest proven oil reserves in the world. According to available data, the country has 303.2 billion barrels, leaving behind Saudi Arabia (267.2 billion) and holding reserves almost seven times those of the United States. Theoretically, with current crude oil prices, every Venezuelan citizen could enjoy a standard of living comparable to that of the Persian Gulf states.

Hyperinflation: The Anatomy of an Economic “Bomb”

The Maduro presidency was characterized by the questioning of the independence of the Central Bank of Venezuela (BCV), which was transformed into a mechanism for financing deficits through reckless money printing practices. The inflation chart below is the “cardiograph” of the fiscal crisis in the country and reveals the extent of the economic devastation experienced by households. From a level of 21% in 2012, the country has been on a meteoric rise. The landmark year is 2018, when inflation reached an unimaginable 65,374%. The purchasing power of the country’s citizens has been wiped out in a very short period of time. The forecast for 2026 remains in triple digits (682%), proving that the economy remains deeply weak. The reality for Venezuelans, however, has been a de facto dollarization. According to estimates, over 50% of transactions in urban centers are now made in US dollars. This has created a two-tier society: A small elite with access to foreign exchange and living in a “bubble” of consumption, and the vast majority of civil servants and pensioners who are paid in Bolívars and live below the poverty line.The “Great Exodus” from the country

Migration data reveals the human cost of the political and economic situation in the country. As shown in the third graph, the flight curve coincides with the explosion of inflation. In 2018, the year when inflation tore apart the social fabric, the most massive exodus was recorded: 1,355,602 people left the country in just one year.How many people have fled Venezuela in recent years?

According to the R4V platform (the coordinating body of the UN Refugee Agency and the IOM), the total number of displaced Venezuelans now exceeds 7.9 million. This is almost 25% of the country’s total population. The regime tried to control the population through the “Carnet de la Patria” (homeland card), linking the CLAP food distribution to political loyalty. However, as the graphs show, hunger and lack of prospects were stronger motivators than fear or dependency. An often overlooked element is the country’s economic dependence on those who have fled. Remittances (remesas) have become a key pillar of GDP, exceeding 5-6% of Gross Domestic Product. For millions of families left behind, the $50 or $100 a month sent by a relative from Miami, Madrid or Bogotá is the only line of defense against hunger. The most worrying element for 2026, highlighted in reports by Human Rights Watch and international think tanks, is the qualitative dimension of this migration. Venezuela has suffered an irreversible brain drain. Petroleum engineers, specialized doctors, university professors and technicians are now scattered in Colombia, Peru, Spain and the United States, among others. The country has lost the human capital that would be essential for any reconstruction effort. Hospitals operate with minimal staff and often without water or electricity, while universities, once centers of excellence, are teeming with professors paid less than $10 a month.The burden of the next day

The Venezuela of 2026 is not simply entering a phase of reconstruction, but a period of peculiar energy “guardianship.” The rapid developments of January, with the direct American intervention and the removal of the previous leadership, have created a new fait accompli: The key to oil flows now lies in Washington, not in Caracas. The White House’s announcement of “indefinite” control of Venezuela’s oil sales, with the proceeds going to controlled accounts, attempts to untie the Gordian knot of corruption, but it creates a titanic financial bet. According to the latest report by Rystad Energy (January 2026), a full recovery of production to 2 million barrels requires mammoth investments of $183 billion by 2040. This is precisely where the big risk lies. Despite pressure from the US government on oil giants (ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips) to return to the country, the response has been cautious. With the exception of Chevron, which has maintained the advantage of staying in the country, the other players are asking for legal guarantees before pouring capital into a country with a broken infrastructure and unclear institutional status. The bet on recovery will therefore not be decided only in the oil fields of the Orinoco zone, but in the courts of New York and in the meetings of international organizations.Please follow and like us: